Preventing Commercial Food Loss:

What Cities and Businesses Can Do to Minimize Their Surplus Food

Written By: Michael Spencer & Jiamin Huang

Abstract

Making the most of available food by minimizing how much is lost will become increasingly important as populations grow. This paper first analyzes three unique programs - Daily Table, D.C. Central Kitchen, and the San Francisco Composting Program - as well as their approaches to minimizing the amount of food lost by commercial sources such as farms, grocers, and restaurants. Using the Triple Top Line model in conjunction with quantitative and qualitative metrics, this study found that the San Francisco Composting Program and D.C. Central Kitchen are focused on environmental and social impact, respectively, while Daily Table is optimized for economic impact. From this analysis, the paper developed a comprehensive list of best practices for similar organizations as those above, the most important of which include: building community support through education and outreach, building mutually beneficial partnerships, and lastly, having a strong understanding of any ethical dilemmas that may surface due to the program’s operations. These results and the subsequent list of best practices can be used as guidelines for any cities or organizations looking to implement sustainability programs in the future, helping them to be as effective as possible.

Introduction

Each year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the United States wastes 133 billion pounds of food, much of which is perfectly edible. A third of this food comes from commercial sources such as restaurants and grocery stores, amounting to an estimated $50 billion in food that is needlessly thrown into the landfill (Buzby, Jean C., et al, 2014). Left to rot, this food produces methane, carbon dioxide, and other damaging greenhouse gas pollutants. Moreover, if it could be collected and used, rather than thrown away, the excess food produced by commercial sources alone would be enough to provide Americans an extra 190 million meals every single day - enough food to feed all of the country’s children two-and-a-half meals daily. As a pressing economic, social, and environmental crisis, the problem of commercial food waste begs for effective solutions. Several organizations and programs are attempting to address this problem; however, many have fallen short or failed outright. To determine best practices for future programs, this report analyzes current programs, of which there are many, as well as their benefits, pitfalls, and structures.

In analyzing our highlighted case studies, it is important to note that they are only a small sample of potential solutions. Sustainable efforts vary from simple guidelines put forth by industry associations to hard policy undertakings by local governments. There are even commercial products that leverage food surplus as feed stock, such as clothing dye made from pomegranate rinds (Dreizen, Charlotte, 2018). That said, the solutions we have chosen are all programs undertaken by either nonprofits or local governments, which tend to be better documented and thus easier to analyze.

Specifically, this report includes three case studies: Daily Table in Dorchester, Massachusetts, the D.C. Central Kitchen in Washington, D.C., and the San Francisco Composting Program. The first, located in a low-income suburb of Boston, looks to provide its community members with healthy produce and meals at discounted rates. The second, a nonprofit kitchen and culinary program, provides job training for recently incarcerated, homeless, or recovering adults, all while using food from commercial partners that would have otherwise gone to the landfill. Lastly, the San Francisco Composting Program partners with a waste recovery company, Recology, to turn San Francisco’s excess food and organic matter into compost for use by local farms.

While there are many options for evaluating these programs’ success, this report utilizes the Triple Top Line (TTL) framework due to its inclusion of economic, environmental, and social perspectives. Unlike other circular economy frameworks, such as Cradle to Cradle, which is intended for use with specific products, or the Blue Economy, which has a strong environmental emphasis, the TTL framework covers all relevant perspectives on these programs. That said, each program’s effectiveness has been evaluated using several key metrics related to the TTL framework, such as: net operating cost, pounds of food rescued per year, estimated food rescue rate, metric tons of CO2 avoided per year, number of meals or tons of compost provided per month, number of jobs created, and complexity.

From the results of the case studies and research, the following report summarizes the findings as a list of best practices and things to avoid. The two lists are meant to be recommendations for any organizations or cities considering implementing such programs, as the authors of this report firmly believe there are lessons to be learned from current programs which can be used to improve the effectiveness of future programs.

Background

To appreciate the gravity of the problem, we have to look beyond just its scale, specifically, to the types of food being wasted. According to a study conducted by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in Denver, Nashville, and New York City, over 50% of the food discarded in these cities is typically edible (Hoover, Darby, 2014). Of this edible food, the NRDC found that almost 40% consisted of fruits and vegetables. Given that almost 15% of American households are food insecure, meaning they lack the ability to buy a sufficient amount of food, this waste of fruits and vegetables - which are both healthy and nutritious - exemplifies the core motivations of many food rescue programs (Buzby, Jean C., et al, 2014).Figure 1: Proportion of wasted food by edibility and proportion of edible wasted food by type.

To understand how to solve the problem of wasted food, we have to know where the food is wasted. Food loss occurs at many points along the food supply chain, mainly at the farm, retail, and consumer levels. Displayed on the next page is a graphic that shows the percentage of food that is lost at each stage in the chain, using data obtained from the World Resources Institute (Lipinski, Brian, 2015). At the farm level, food waste can occur due to rejection of products under to safety standards, the incineration of byproducts from food processing, spillage from faulty equipment, and the rejection of products under cosmetic standards by buyers. At the retail level, waste is caused by damaged packaging, inadequate storage, the discarding of blemished food, and overstocking or over-preparing food that ultimately doesn't get bought. Finally, at the consumer level, food is wasted for reasons ranging from improper storage to a misunderstanding of “use-by” dates to simple aversion to certain foods. As can be seen from the causes of food loss, it’s impossible to expect that one hundred percent of waste can be avoided. However, there are areas that show great potential to be eliminated using circular interventions, such as food that fails cosmetic standards and overstocked food at grocery stores.

Figure 2: Percentage of food lost at each stage in production and consumption.

Research & Case Studies

Research Methods and Metrics

As part of this report, the case studies below were evaluated using several key metrics based on the Triple Top Line (TTL) Circular Economy Framework. As mentioned, this framework was chosen for use in this project due to its focus on three key principles - ecology/environmental, economic, and equitable social impact.

At their root, sustainability programs are environmentally focused, meaning that in order to be effective, they must make a significant impact in reducing damage to the environment, hence the inclusion of the first principle in the TTL framework. That noted, these types of programs often require the support of the local community and its economy, meaning that effectiveness also relies on a program’s financial feasibility and potential social impact. To that end, an ideal program performs well across all three aspects of the TTL framework, hence its use in this report. The following metrics are closely tied to each aspect of the TTL framework and will be used to measure the effectiveness of the included case studies:

Net Operating Cost: This measure allows for a quantitative understanding of the economic feasibility of implementing the program or organization, and is useful in determining how easily a similar model could be implemented elsewhere. As this is a measure of economic feasibility, the lower a program’s net operating cost is, the better.

Pounds of Food Diverted per Year: This measure, in conjunction with the next, allows for a quantitative understanding of a program’s impact and circularity. As this is a measure of environmental impact, the higher it is, the better.

Estimated Food Diversion Rate: This measure uses the pounds of food rescued or diverted per year to determine the impact and circularity of a program or organization. It is calculated by measuring how much commercial food loss is present within the locality where a program is implemented. The amount of food rescued or diverted by the program is then divided by the total commercial food loss in the local area to determine what proportion of wasted food the program or organization potentially diverted from landfills. As this is a measure of environmental impact, the higher it is, the better.

Metric Tons of CO2 Avoided per Year: This measure allows for a quantitative understanding of a program’s environmental impact. Perhaps unknown to many, the degradation of lost food in landfills produces large amounts of methane and CO2, adding to already increasing greenhouse gas emissions. As the effects of greenhouse gases are felt by communities outside of those in which they are produced, this metric allows for easy comparison of the case studies without any additional contextualization. To standardize units and gain a better understanding of the overall impact of greenhouse gas emissions, all measures (for example, the amount of methane produced) will be converted to MTCO2 per year. As this is a measure of environmental impact, the higher it is, the better.

Meals/Tons of Compost Provided per Month: This measure allows for a quantitative understanding of a program’s social impact and ability to be equitable within the community it serves. In the report below, this measure will be framed in the context of the case study to better understand the impact made within a given community. As this is a measure of both environmental and equitable social impact, the higher it is, the better.

Jobs Created: This measure allows for an understanding of a program’s social impact and ability to influence the economy of its surrounding community. In many cases, it has been found that sustainable alternatives to linear systems create more jobs than were originally available. This is largely due to the more complex processes involved in reusing and recycling materials. With this in mind, programs will be compared by their ability to create jobs within the community surrounding them. As this is a measure of both environmental and equitable social impact, the higher it is, the better.

Complexity: This measure is used to quantitatively understand the scale and intricacies of a program. It is measured on a 5-point scale with 5 being most complex and 1 being least complex. Certain factors that will be considered in determining a program’s complexity include, but are not limited to, how many locations it operates, how many people it serves, how many people it employs, how many partners it requires, and its dependence on funding from outside sources. This is largely an economic measure, and in general, the lower it is, the better.

- - - -

Case Studies

Daily Table (Dorchester, Massachusetts) - Nonprofit Grocery Store

Daily Table is a pair of nonprofit grocery stores operating out of Dorchester, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston with a population of 90,000 (“Daily Table – Dorchester,” 2018). The stores sell staple food items to local community members, many of which are from low-income backgrounds. Before diving into the analysis and performance of Daily Table over the key metrics discussed earlier, it is important to understand the basic structure, mission, and beginning of the organization. abc

Figure 3. Daily Table in Dorchester, Massachusetts

Daily Table opened its doors in 2015, at which point it began to sell staple food items at a steep discount. It was founded by Doug Rauch, former president of Trader Joe’s, in an effort to “reduce both the effects of poor eating habits caused by challenging economics, and the impact that wasted food and its precious resources has on our environment.” With this goal in mind, many of the food items are sourced from other commercial retailers, such as grocers and restaurants, as well as local farms. Much of this food is surplus food unwanted by partners due to its nearing “sell-by” date or visual imperfections, meaning it is effectively “rescued” by Daily Table. In addition, Daily Table accepts food donations, and when needed, will purchase food at discounted rates from commercial partners to meet demand (“Daily Table – FAQs,” 2019). It is with this that Daily Table becomes a member of the circular economy and in turn, a viable case study.

Due to the nature of their food source, Daily Table is able to operate a fully functional grocery store while maintaining low prices for the community members shopping there. It’s not unusual to see a gallon of milk sell for less than $1, nor to see other staple goods sell for half of what they usually cost. Despite these steep discounts, however, Daily Table offsets roughly 75% of their operating costs through the revenue generated from sales, which also includes pre-prepared meals created from the surplus food they stock. It’s important to note that the additional ~25% of operating costs are offset by foundation funding, making Daily Table extremely feasible from a financial standpoint (“At Daily Table Grocery Store, A Business Model Powered By Wasted Food”, 2015).

As part of its business model, Daily Table also employs roughly 61 people, 80% of which are members of the Dorchester community (Meredith Somers, 2018). Thus, in addition to having a fairly sustainable business model, Daily Table is able to do so while providing economic value to the community around it. In providing jobs to several community members, Daily Table provides a steady form of income to its workers, many of which face economic challenges. This type of impact is categorized as equitable and social, and will be reflected as such in later comparisons.

Turning to Daily Table’s environmental impact, analysis was done to recognize the amount of surplus food the organization was able to rescue. Since opening in 2015, Daily Table has recovered an average of 1.3 million pounds of food per year. This is measured by aggregating the total food rescued from all commercial partners, including but not limited to, grocery stores, restaurants, manufacturers, and local farms. Using this data, estimates can be made to determine how many meals are provided on a monthly basis, how many tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are avoided annually, and most importantly, the relative proportion of food saved from landfills. A recent Daily Table case study performed by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimates that the food rescued by Daily Table, in conjunction with what is purchased, is enough to provide 600,000 meals monthly to the local community (Yerina Mugica, 2017). This is enough food to feed roughly 1,000 people 3 meals a day. Additionally, by analyzing the total annual commercial food loss in Dorchester, it can be shown that Daily Table helps divert 8-15% of food away from landfills. All-in-all, this avoids the creation of 1,113 metric tons of CO2 emissions annually, as reported by the same NRDC report. This is equivalent to removing roughly 240 cars from the road (US EPA, OAR, OTAQ, TCD, 2018). Given the small scale of Daily Table’s operation, the latter metrics are promising.

As Daily Table operates as just a couple stores, serving a relatively small town, with a straightforward business model and limited funding from outside sources, we gave the program a 2 out of 5 on our complexity scale. Due to the number of partners that Daily Table needs to operate, it is not the simplest program to run; however, we feel that the connections with these partners and the store operations take up the vast majority of Daily Table’s organizational and managerial resources.

A summary of what was found in this case study is provided in the following chart:

Figure 4: Summary of Daily Table’s performance over given metrics.

D.C. Central Kitchen (Washington D.C.) - Revenue-Generating Nonprofit

The D.C Central Kitchen, often referred to as DCCK, is a revenue-generating nonprofit which operates out of the Washington, D.C. area. The organization partners with local farms, food retailers, food wholesalers, homeless shelters, and schools to provide culinary training and pre-prepared meals to its community members, of which 92,000 struggle with hunger and/or food insecurity. Central to the organization is the belief that hunger stems from poverty, and to solve the former, you must address the latter. With this in mind, all of their culinary students are adults recovering from homelessness, incarceration, or addiction.

The D.C. Central Kitchen opened its doors in 1989, at which point it was operating out of the basement of a homeless shelter. Since then, DCCK has partnered with various local organizations to commandeer their kitchens at times when they would otherwise go unused. The additional capacity has allowed the organization to begin servicing local public schools and corner stores with healthy meals, even catering events on occasion. The organization’s founder, Robert Egger, was a former nightclub owner who had become fed up with the complacency surrounding hunger and poverty in the D.C. area. He understood that hunger could be tackled by minimizing the amount of food going to landfills, but he also hoped to fight hunger at its source - poverty and a lack of means to purchase healthy food. Sticking close to this goal, DCCK sources its food similarly to Daily Table above. Many items are sourced from commercial retailers, local farms, colleges and universities, as well as wholesale distributors. A large part of this food is excess - it would have been wasted had DCCK not rescued it - however, some is purchased at discounted rates. Participation in the reclamation of food from these sources allows DCCK to recirculate food throughout the economy and local community, all while having an equitable impact (Yerina Mugica, 2017).

Via their social enterprises, the D.C. Central Kitchen is able to cover almost 60% of their operating expenses. These services include Fresh Start Catering, Healthy School Food, and Healthy Corners, which, allows DCCK’s culinary program to provide events, schools, and local stores with freshly prepared, healthy meals. Additional funding comes from foundation grants, individuals, corporate partners, governmental grants, and varying types of events. The exact proportions can be seen in the chart above. As a whole, this breadth of funding makes the D.C. Central Kitchen appealing as a means of reducing commercial food waste, as it is economically feasible to implement with some scaling.

Turning towards the impact that the DCCK has on its local community, this study found that the organization is making substantial headway towards equitable, environmental, and scalable change. Through its 14 week culinary training program, the organization graduated 91 culinary students in 2016, 1,400 total since it first started. Of these students, 88% found and retained jobs upon graduation (D.C. Central Kitchen, 2016). Not to be missed, the program also recovered roughly 830,000 pounds of food in 2017. In their annual impact report, the D.C. Central Kitchen reported that the food which was recovered, along with that purchased, allowed the program to provide roughly 3.2 million meals in 2017. Measured out, this is enough to feed 3,000 people 3 meals a day - an important fact given the number of D.C. residents suffering from hunger.

Environmentally, the D.C. Central Kitchen helps to divert roughly 2-5% of local commercial food away from landfills. In comparison to Daily Table, this may seem insignificant, however it is important to remember that Washington D.C. is significantly larger than Dorchester, and as such, produces much more waste.

Because the D.C. Central Kitchen operates such a variety of services and requires partnerships with several different organizations to source food, get funding, and find customers, we gave DCCK a 4 out of 5 on our complexity scale. Beyond the manifold dimensions of the program, DCCK also serves the sizable population of Washington, D.C., further justifying its rating.

As with the previous case study, all metrics for the D.C. Central Kitchen are summarized below:

Figure 6: Summary of D.C. Central Kitchen’s performance over given metrics.

San Francisco’s City-Wide Composting Program (San Francisco, California) - Municipal Waste Management

The inception of San Francisco’s modern curbside composting program began in 1996, when the city first began collecting food waste from restaurants (“Myths about Recycling in San Francisco,” 2017). During the next thirteen years, the city rolled out policy initiatives including asking residents to voluntarily separate their waste, incentivizing businesses to recycle and compost more with discounts on their trash bills, and pledging to reach zero waste by 2020. These efforts by the city ultimately culminated in the nation’s most comprehensive mandatory composting law in 2009, when San Francisco passed the Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance. This ordinance requires every resident, business, and property manager in the city to sort their trash, recyclables, and compostables into three separate bins, called the “Fantastic Three.” Through this gradual buildup of legislative support, San Francisco now operates one of the most successful citywide curbside composting programs in the U.S.

To handle the logistics and operations of this program, San Francisco public agencies partner with Recology, the local waste management company that is currently the exclusive provider of waste collection services in the city. Residents and businesses in the city pay a fee, set by the S.F. Department of Public Works, to Recology to collect, haul, and process all three forms of waste. With regards to organic waste in particular, Recology transports the waste to nearby composting facilities, such as the Jepson Prairie Organics Facility. These high-capacity compost plants use the organic waste as feed stock to produce Recology’s own line of compost products, which are then sold to local farms and Napa vineyards (“Recology Organics,” 2018).

As previously mentioned, collection rates are determined by the Department of Public Works, which draws on historical example and incorporates financial incentives to encourage residents and businesses to compost and recycle more. For example, businesses have the potential of saving up to 75% on their trash bill if they opt to reduce the size of their landfill bin or the number of times their waste is collected per week (“Recycling & Composting in San Francisco - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” 2017). There are similar incentives for residents, who can lower their monthly bill from $40.04 for three 32-gallon bins to $33.78 if they reduce the size of their trash bin to 16 gallons (“Residential Rate Calculator,” 2018).

Besides setting the monthly collection fees, the city is also responsible for education, outreach, and enforcement among residents and businesses, which is handled by the Department of Environment, otherwise known as SF Environment. SF Environment’s Environment Now team conducts door-to-door auditing and outreach, checking the bins of residents and businesses to ensure that waste is being properly sorted. If improper sorting is found, the team leaves a notice to inform the resident or business of the correct bin and will follow up the next week to check for compliance. Although fines of up to $100 for residents and $1,000 for large businesses can be imposed for repeat offenders, the city makes an effort to prioritize education and outreach instead to encourage compliance (Wollan, Malia, 2009). As such, SF Environment invests in multilingual educational materials, posters, signage, and trainings in order to ensure that everyone in the city is properly informed of where their waste belongs.

As a large-scale, comprehensive waste collection program, San Francisco’s composting and recycling deal with Recology has a significant cost. In 2015, the city awarded Recology a contract worth $130 million to operate in the city over the next decade (“San Francisco Did the Right Thing on Garbage Contract - San Francisco Chronicle,” 2015). The money collected in fees from residents and businesses is used to fund everything from Recology’s composting facilities to its infrastructure upgrades to SF Environment’s educational outreach programs. Additionally, San Francisco residents are already feeling the burden of rising costs, as the city just last year approved a request from Recology to raise rates by an average of 14% (Swan, Rachel, 2017).

However, these costs do allow San Francisco to ensure that every resident in the city has equal access to their curbside composting program. On top of the door-to-door outreach initiative, SF Environment also ensures that information is found is a variety of different languages. Their website alone is available in English, Mandarin, Filipino, and Spanish. Furthermore, low-income residents are eligible for a 25% discount on their collection fees, and disabled residents can get their waste picked up from indoor locations at no extra cost (“Recycling & Composting in San Francisco - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” 2017). Beyond just San Francisco and Recology’s efforts to include everyone in curbside composting, the program itself has created over 1050 jobs ( “Zero Waste - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” 2017). This number is likely a significant underestimate as well, since it only includes employees of Recology in San Francisco alone, and does not account for corporate employees or employees in the processing facilities outside of San Francisco.

San Francisco’s curbside composting program makes its largest impact in the environmental sphere. Annually, the program diverts 255.5 million pounds of food waste from landfills each year, which we calculated to be about 50% of the total food discarded in San Francisco. This translates into 93,437 metric tons of CO2 equivalent avoided over a year, which has the impact of removing over 20,300 passenger vehicles from the road. The collected food waste also makes an impact when it is processed into compost. From just the food scraps gathered from San Francisco, Recology is able to produce 9000 tons of compost a month (Mugica, Yerina & Andrea Spacht, 2017). This amount of compost is enough to fully fertilize ten vegetable farms, helping to close the loop on food waste.

Due to the large scale and multidimensional requirements of this program, we gave San Francisco’s curbside composting program a 5 out of 5 on our complexity scale. Given the amount of legislation, infrastructure, and day-to-day management needed to both get this program off the ground and keep it running, we believe a 5 is well-deserved.

As with the prior two case studies, a summary of the metrics found is displayed below:

Figure 8: Summary of S.F. Composting’s performance over given metrics.

Analysis

Each of these case studies provides unique insights into the challenges and demands of trying to capture excess food with circular interventions. Given the vastly different areas of focus and strategies of each program, we will evaluate each case study individually for their strengths and weaknesses before doing a direct comparison of the three.

As previously seen, Daily Table targets its intervention at the higher levels of the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy, shown below, by collecting perfectly edible but otherwise unused food and selling both raw produce and pre-prepared meals to its customers for consumption. As a relatively small but well-organized and well-connected operation, Daily Table should be applauded for its multidimensional impact. In addition to diverting needlessly discarded food from landfills, it provides low-income residents with the ability to eat healthily on a budget. Furthermore, Daily Table has shown that it truly cares about the community members it is serving, making sure to hire from the surrounding neighborhood and welcoming continuous feedback from its customers. Its establishment of an in-store kitchen to prepare healthy packaged meals was a response to customer needs, as residents coming home after long days at work preferred meals they didn’t have to prepare themselves. This swift responsiveness to the community has contributed significantly to Daily Table’s continued success. Additionally, the self-sustaining cost structure of Daily Table’s operations provides a model for future programs trying to rescue food at low cost.

However, as effective as Daily Table has been at such a small scale, there are still potential concerns with its model that must be noted. For one, Daily Table has a strong reliance on the presence and willingness of other businesses to form partnerships with, since their food would have to be sourced entirely from donations and purchases otherwise. As a result, an attempt to start a similar model in a more rural location with fewer available potential partners would likely find it ultimately infeasible. On the other hand, the presence of a Daily Table-type program in a location with many other charitable programs such as food banks could cause cannibalization to arise. Without clear communication with other nonprofits, it’s entirely possible that Daily Table could poach food that would otherwise be donated to homeless shelters and food banks, which serve different needs. Finally, it is also unclear what is done with the unused food that Daily Table produces. Since it is still essentially a grocery store, there must be some amount of food surplus that is not sold; however, Daily Table is not transparent about what is done with this food. Given the underlying principles of the store, we hope that this excess food is composted in some way, but we were not able to confirm that for sure.

Moving onto the other private nonprofit, the D.C. Central Kitchen provides a good example of an organization that also tries to close the loop on wasted food, but with a distinctly different approach. Like Daily Table, the D.C. Central Kitchen also intervenes in food loss at a higher level on the hierarchy, rescuing food from other businesses to use in a variety of services. Unlike Daily Table, DCCK casts a wide net in its programming, offering everything from catering services to meal preparation and delivery to culinary training. With this array of operations, DCCK is able to address food waste as well as hunger and poverty in the community. Moreover, it’s already been proven that DCCK’s model is replicable in other cities. A sister kitchen has already opened in Los Angeles, with the same culinary training program for incarcerated and homeless adults, but a focus on serving the elderly instead. Additionally, unlike Daily Table, DCCK makes a transparent and conscious effort to put their own waste to use, composting organic waste, recycling other materials, and sending their used cooking oil to be turned into biofuel.

Given its extensive operations, it’s no surprise that D.C. Central Kitchen’s relative complexity provides some challenges to any program trying to emulate its model. As discussed previously, DCCK’s origin began in the kitchen of a homeless shelter, and any future program will likely have to form similar agreements for existing kitchen usage in order to get started at low cost. To even emulate DCCK’s current cost structure, where the majority of costs are covered by its own revenue, future programs must think big and incorporate many different types of services to offer to the community. However, establishing a job training service, a catering service, and a meal preparation service is no small task and will require strong leadership and organization to manage effectively.

Finally, we turn to San Francisco’s composting program to draw lessons from this multifaceted public-private partnership. While the program encompasses the entire city of San Francisco, making its scale significantly larger than either Daily Table or the D.C. Central Kitchen, composting is also a less-preferred intervention on the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy. Regardless, while it may be preferable to rescue unused food, food scraps still present a huge opportunity for circular intervention due to the current sheer volume of food we’re throwing away. Due to the large scale of the program, the environmental impact of the food waste that San Francisco is able to turn into compost for later productive use is simply enormous. In addition, San Francisco is looked up to as a model around the country for the high compliance it’s achieved, which is motivated by the symbiotic combination of policy mandates, financial incentives, and extensive education. Instead of imposing a heavy-handed dictate on citizens, San Francisco and Recology have worked to incorporate curbside composting seamlessly into their lives, so a mandate to compost seems less like Big Brother and more like a common-sense way to handle organic waste. As such, this combination has enabled San Francisco to make significant progress towards its goal of zero waste in just the last fifteen years.

Yet even as San Francisco is held up as the city on a hill, other municipalities must keep in mind the factors already in place that allowed San Francisco to achieve this success. Primarily, San Francisco had the infrastructure and logistics in place to roll out this program smoothly. Recology, previously NorCal Waste Systems, Inc., had been operating in the city for decades. Unlike in many other major cities in the U.S., three high-capacity composting plants are located within 100 miles of San Francisco, enabling Recology to truck and process organic waste at lower costs (“Recology Organics,” 2018). As a result, any city without this sort of infrastructure looking to implement a curbside composting program of this scale would face significant hurdles right away, as they’d have to figure out how to lay the foundations and negotiate with potentially competing waste management companies first. Along similar veins, a city with this aspiration would also have to throw strong political and legislative support behind the mission. As discussed earlier, San Francisco experimented with a series of policies encouraging composting and recycling before finally throwing their weight behind a strict mandate. Without this mandate and the educational outreach alongside it, it’s difficult to imagine that as many residents and businesses in San Francisco would be properly sorting their waste today.

Looking at all three case studies side-by-side, we can use our metrics for each program to draw larger conclusions about their differences in effectiveness. As a caveat, since these programs are so disparate and have distinct contexts, systems, and goals, direct comparisons of the numbers should be taken with a grain of salt. Instead, we’ll use a comparison of the metrics to inform a more general analysis of how these programs stack up against each other. For reference purposes, a comparison table of all three case studies is displayed below.

Figure 10: Comparison table of the three case studies.

Perhaps the first thing to stand out from this table is the stark differences in scale between the SF Composting Program and our two nonprofits, Daily Table and the D.C. Central Kitchen. Immediately, we can see that the curbside composting program imposes a much larger net cost, but has a much larger environmental impact in the number of pounds of food diverted, the food diversion rate, and the amount of CO2 avoided per year. In particular, the food diversion rate, which measures the circularity of a program within the context of its location, shows that the San Francisco Composting Program is significantly more impactful in capturing the use of food waste than our nonprofits. We believe this can be attributed to two factors: first, San Francisco operates near the bottom of the food recovery hierarchy, capturing any form of food that is to be thrown away, whereas Daily Table and DCCK specifically target edible food that is needlessly thrown away. Second, since San Francisco has publicly devoted itself to zero waste, by nature this program has the backing and support of the local government with a primary focus on waste diversion and a more secondary focus on cost and social impact.

As such, much more money, time, and effort can be spent by the city of San Francisco on convincing residents and businesses to compost, while the actual logistics are handled by Recology. Daily Table and the D.C. Central Kitchen simply do not have the money to devote to capturing every pound of food they can use, nor would that necessarily align with their goals. Daily Table’s core goal is to take otherwise unsold and wasted food and sell it at a discount so the residents of Dorchester can eat healthily. On the other hand, D.C. Central Kitchen’s core goal is to address hunger and poverty, doing so through the collection of unused food to prepare meals and train adults in culinary skills. As we can see, neither program is looking to eliminate food waste. Rather, they use wasted food as a way they can improve their communities. Overall, while San Francisco makes a splash environmentally, Daily Table and D.C. Central Kitchen are much more socially focused, providing meals and jobs for their community with the food they rescue.

Even between Daily Table and the D.C. Central Kitchen themselves, we can see how differences in missions alters the types of impacts each program ultimately makes. Daily Table in essence operates as a business, making sure to keep costs low and revenues up so it can be a self-sustaining nonprofit. Even though Daily Table only opened in 2015, it’s already covering 75% of its business expenses, whereas the D.C. Central Kitchen has been in operation since 1989 and now only covers 60% of its expenses. Yet, D.C. Central Kitchen has enabled the employment of 1,400 adults, compared to Daily Table’s 61. Between the two programs, we can clearly see that DCCK has a much more hands-on social focus than Daily Table does, causing it to run less like a business in comparison. This difference in focus is reflected in the numbers, and should be considered by future programs when they consider what their ultimate goal is. Overall, we can see that tradeoffs must be made between environmental impact, economic costs, and social benefit. Therefore, the first question any program looking to divert food waste must ask itself is, what matters most? Is it to keep as much food as possible out of landfills? Is it to build a self-sustaining operation that can be run cost-effectively? Or is it to serve the community as best as possible? Determining this answer will allow the program to best design its service to achieve the impact it wants. No one program can do it all, and do it all well.

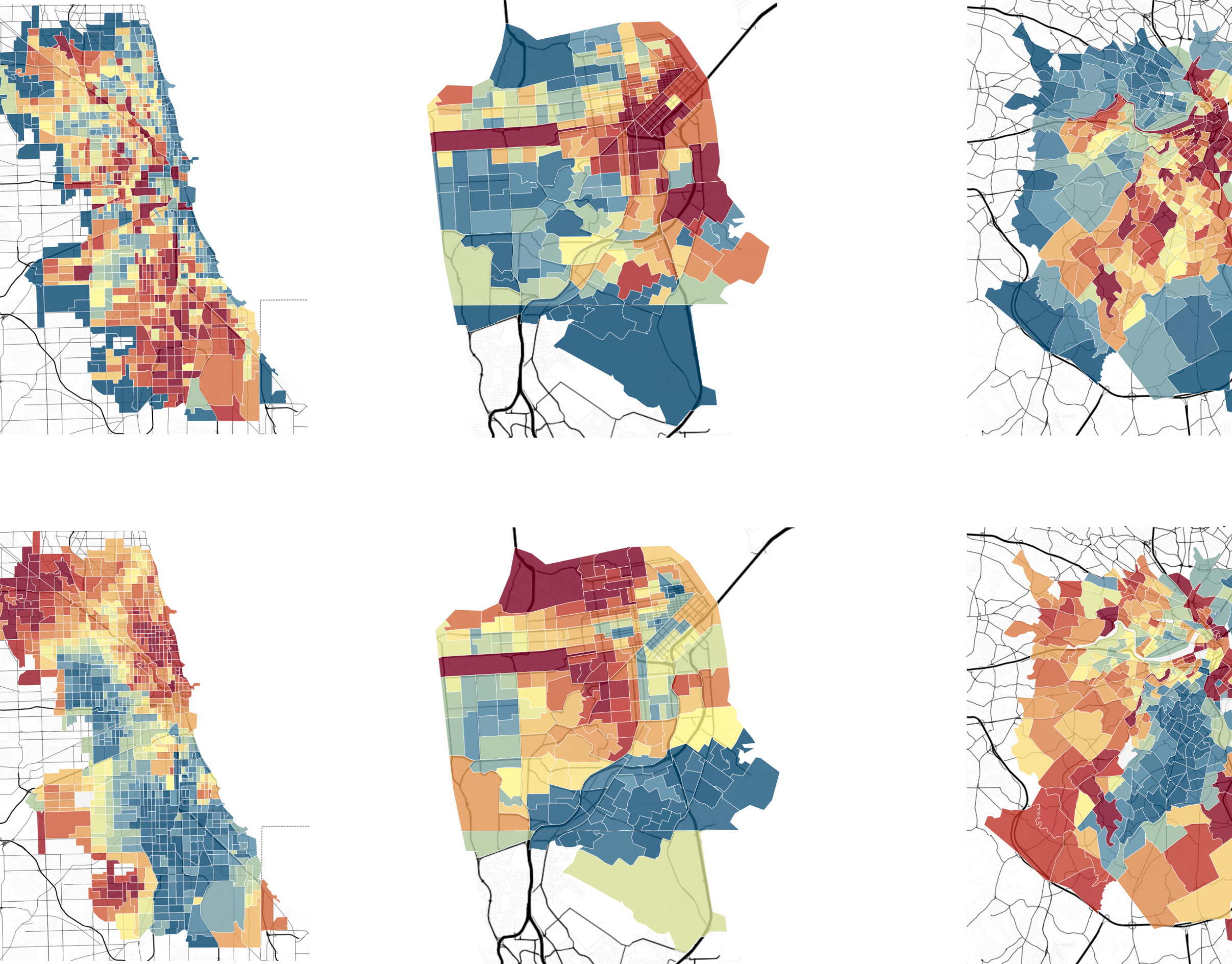

To determine how well each of the case studies in this report balance the three factors discussed above, they were placed within a fractal triangle used to represent the Triple Top Line framework referenced earlier (Design for the Triple Top Line, 2002) .

Figure 11: Each case study situated in the TTL framework.

Beginning from the left to right, the San Francisco Composting Program, in partnership with Recology, falls within the ecological sub-triangle above. This decision was made due to the program’s large environmental impact relative to the other two case studies. Further, it was determined that the program’s emphasis on cost-effectiveness far outweighed its emphasis on equitable impact, thus leaving it to be placed closer to the economic sub-triangle than that of the equity sub-triangle.

Daily Table on the other hand falls within the economic sub-triangle of the TTL fractal. This decision was made due to the programs’ emphasis on cost-effectiveness and being financially accessible to its local community members. Internally, the organization focuses more on its equitable and social impact than it does its environmental footprint, causing it to be placed closer to the equity sub-triangle than to that of ecology.

Finally, D.C. Central Kitchen was placed within the equity/social sub-triangle of the TTL fractal. This was in large part due to the organization’s integration of a culinary training program into its everyday operations. Through this program, they were not only able to find a use for the food they rescue, but they were able to do so in a manner that provided job-training skills to their local community members, thereby generating a positive social impact. With that in mind, DCCK’s operations have more of an emphasis towards sourcing their food from environmentally friendly sources than they do being cost-efficient, placing the organization closer to the ecological sub-triangle than the economic one.

Recommendations

Although any future program will have to choose its mission carefully and structure its operation to align with its individual goals, we have compiled a list of recommendations that we believe have helped all three case studies we investigated achieve success. Alongside this list of best practices, we also propose a list of potential pitfalls that programs may encounter, which may significantly hinder the effectiveness of their mission.

Best Practices

Build community support through education and outreach.

All of the case studies we investigated have strong ties to the local community. Through efforts to engage with and educate community members on the principles of their operation, these programs ensure they have a strong base of support that helps them run smoothly and build connections. This practice was included here due to the fact that it was integral to the success of all of the above case studies. It falls within the social aspect of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not adhering to this practice could make it extremely difficult for organizations and programs to build rapport and trust within their local community.

Build mutually beneficial partnerships with other nonprofits.

The D.C. Central Kitchen engages with other organizations such as homeless shelters and local colleges to incorporate their complementary goals into its own mission, with great success. Using these partnerships, programs can draw upon the resources of already established nonprofits to help establish themselves early on. As was seen in the Daily Table and DCCK case studies, partnerships with local organizations are extremely important to an program’s success. For that reason, this practice was included in this list. It falls within the social and economic aspects of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not adhering to this practice could make it extremely difficult for organizations and programs to operate, particularly if they are seen as competition from other organizations.

Leverage funding from foundations and government initiatives.

Similarly, to support themselves in their early stages, we believe that programs should take full advantage of grant funding. These sources of funds enable programs to take the time to build sturdy organizational foundations at the beginning, and expand their operations later on. This practice was included here due to the fact that it was integral to the success of all of the above case studies. It falls within the economic aspect of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not adhering to this practice could make it extremely difficult for organizations and programs to grow and function, particularly in the first few months of operations.

Start at a scale that makes sense, and prioritize cost-effectiveness early on.

Although many of these programs may have lofty social and environmental goals, they should rein in their aspirations initially and start small. As we saw with all three case studies, building up gradually helps ensure the program is manageable from the beginning and can be run effectively. Ensuring that costs are relatively low will make it easier to expand in the future. As was seen in the Daily Table and DCCK case studies, starting small is extremely important to an program’s success. For that reason, this practice was included in this list. It falls within the economic and environmental aspects of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not adhering to this practice could make it extremely difficult for organizations and programs to become increasingly impactful. Instead, it is possible that these organizations would see early failure.

Secure legislative support for the organization’s goals.

As we saw with the SF composting program, legislation can be a great tool in getting people and businesses to participate in circular interventions. The combination of legislation with outreach and education is an effective way of increasing the level of involvement in your program. As was seen in the San Francisco case study, starting gaining local legislative support is extremely important to an program’s success. For that reason, this practice was included in this list. It falls within the economic, environmental, and social aspects of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not adhering to this practice could make it extremely difficult for organizations and programs to implement the types of programming needed to be effective.

- - - - -

Practices to Avoid

Don’t locate a complex operation in a place with little organizational support.

Without the presence of other businesses, nonprofits, and active governments in its location, a program’s ability to form partnerships and leverage others’ resources disappears. Instead, they’ll be left on their own, with a much lower likelihood of success. As was seen in the above case studies, support from outside organizations is key to success. That said, this “practice to avoid” was included as a warning to those who may try to implement a complex program in a place without the resources and support to help it grow. It falls within the economic aspect of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not considering this would make it incredibly hard for a program to grow and expand.

Don’t forget about other nonprofits that already exist in your space.

Be aware of other organizations with similar missions - they offer opportunities for mutually beneficial partnerships, as mentioned earlier, but additionally no one is helped if each program inadvertently interferes with the other’s operations. From background research, it was found that some failed programs did so because they were competing with other organizations for food, volunteers workers, and funding. That said, this practice was included as a warning to those who may not consider local organizations when setting up their business model. It falls within the economic aspect of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not considering this could spell potential long-term trouble for organizations and programs.

Don’t alienate the people you’re serving with inaccessibility or insensitivity.

If a program doesn’t keep accessibility and community needs at the forefront, they risk turning the people they’re ultimately serving against them. Without the support and engagement of the population, they’ll have a much tougher time accomplishing their goals. Again from background research, it was found that some struggling programs did so because they were unable to service large groups of people, many of which could have benefited greatly from such programming. That said, this practice was included as a warning to those who may not consider all of their potential constituents when setting up their business model. It falls within the social aspect of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not considering this could spell potential long-term trouble for organizations and programs.

Don’t have a savior complex.

Back up the mission with pragmatism. Don’t expect people to buy in just because there’s a feel-good concept. Integrate the service into people’s lives naturally, and provide practical incentives so they’d actually be losing out if they didn’t participate. While not something typically thought about, this practice was included so as to keep organizations and programs in line with socially acceptable practices. A part of the TTL’s social aspect, this practice should be seen as a way for organizations and programs to check themselves and to help them to navigate today’s complex world.

Don’t forget to look for blind spots in programming.

Constantly evaluating its own shortcomings allows a program to see where it can improve, adapt, grow, and innovate. For example, San Francisco could work on finding ways to collect used cooking oil, which is not collected presently, to be turned into biofuel. From background research, it was found that some struggling programs did so because they were unable to accommodate some needed programming. That said, this practice was included as a warning to those who may not consider all of their potential options when setting up their business model. It falls within the environmental, economic, and social aspects of the TTL framework, making it incredibly important for a program using that framework as a guideline for development. Not considering this would not cause any severe problems, however it’s adherence would help to make programs more effective.

With these recommendations in mind, we hope that future programs, whether they are modeled after the case studies we looked at or they take a new approach, are well-equipped to be effective and successful in capturing the wasted food in America and putting it to good use.

WORKS CITED

Adams, Susan. “How Daily Table Sells Healthy Food To The Poor At Junk Food Prices.” Forbes. N.p., 2017. Web. 5 June 2018.

“At Daily Table Grocery Store, A Business Model Powered By Wasted Food | Fortune.” Fortune. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2018.

Buzby, Jean C., et al. The Estimated Amount, Value, and Calories of Postharvest Food Losses at the Retail and Consumer Levels in the United States United States Department of Agriculture. 2014, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/43833/43680_eib121.pdf?v=41817.

“Daily Table – Dorchester.” N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2018.

“Daily Table – FAQs.” N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2018.

D.C. Central Kitchen. “DC Central Kitchen Annual Report 2016.” N.p., 2016. Web. 27 May 2018.

Design for the Triple Top Line (2002) | William McDonough. http://www.mcdonough.com/writings/design-triple-top-line/. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Dreizen, Charlotte. “6 Products Leveraging Food Waste As Feedstock | GreenBlue.” GreenBlue. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 June 2018.

Hoover, Darby. “Report: What, Where, and How Much Food Is Wasted in Cities | NRDC.” National Resources Defense Council. N.p., 2017. Web. 2 June 2018.

Lipinski, Brian. “What’s Food Loss and Waste Got to Do with Sustainable Development? A Lot, Actually.” World Resources Institute. N.p., 2015. Web. 5 June 2018.

Mugica, Yerina, and Andrea Spacht. “Food to the Rescue: San Francisco Composting | NRDC.” National Resources Defense Council. N.p., 2017. Web. 2 June 2018.

Mugica, Yerina. “Food to the Rescue: Daily Table—Rescuing Food and Creating Better Alternatives for Low-Income Families | NRDC.” National Resources Defense Council. N.p., 2017. Web. 16 May 2018.

Mugica, Yerina. “Food to the Rescue: DC Central Kitchen | NRDC.” N.p., 2017. Web. 27 May 2018.

“Myths about Recycling in San Francisco.” SF Environment. N.p., 2017. Web. 4 June 2018.

“Recology Organics.” Recology San Francisco. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 June 2018.

“Recycling & Composting in San Francisco - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).” SF Environment. N.p., 2017. Web. 2 June 2018.

“Residential Rate Calculator.” Recology San Francisco. N.p., 2018. Web. 4 June 2018.

“San Francisco Did the Right Thing on Garbage Contract - San Francisco Chronicle.” San Francisco Chronicle. N.p., 2015. Web. 2 June 2018.

Somers, Meredith. “What Opening a Nonprofit Grocery Taught the Former President of Trader Joe’s.” MIT Newsroom. N.p., 2018. Web. 16 May 2018

Swan, Rachel. “SF Approves 14 Percent Garbage-Pickup Rate Hike - SFGate.” SF Gate. N.p., 2017. Web. 4 June 2018.

US EPA, OAR,OTAQ,TCD. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle. Accessed 2 June 2018.

Wollan, Malia. “San Francisco to Toughen a Strict Recycling Law - The New York Times.” The New York Times. N.p., 2009. Web. 4 June 2018.

“Zero Waste - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).” SF Environment. N.p., 2017. Web. 4 June 2018.